Carrie Parsons

89.5 KVNE Mornings

We can help our kids by giving them a better understanding of natural disasters and how they affect our faith.

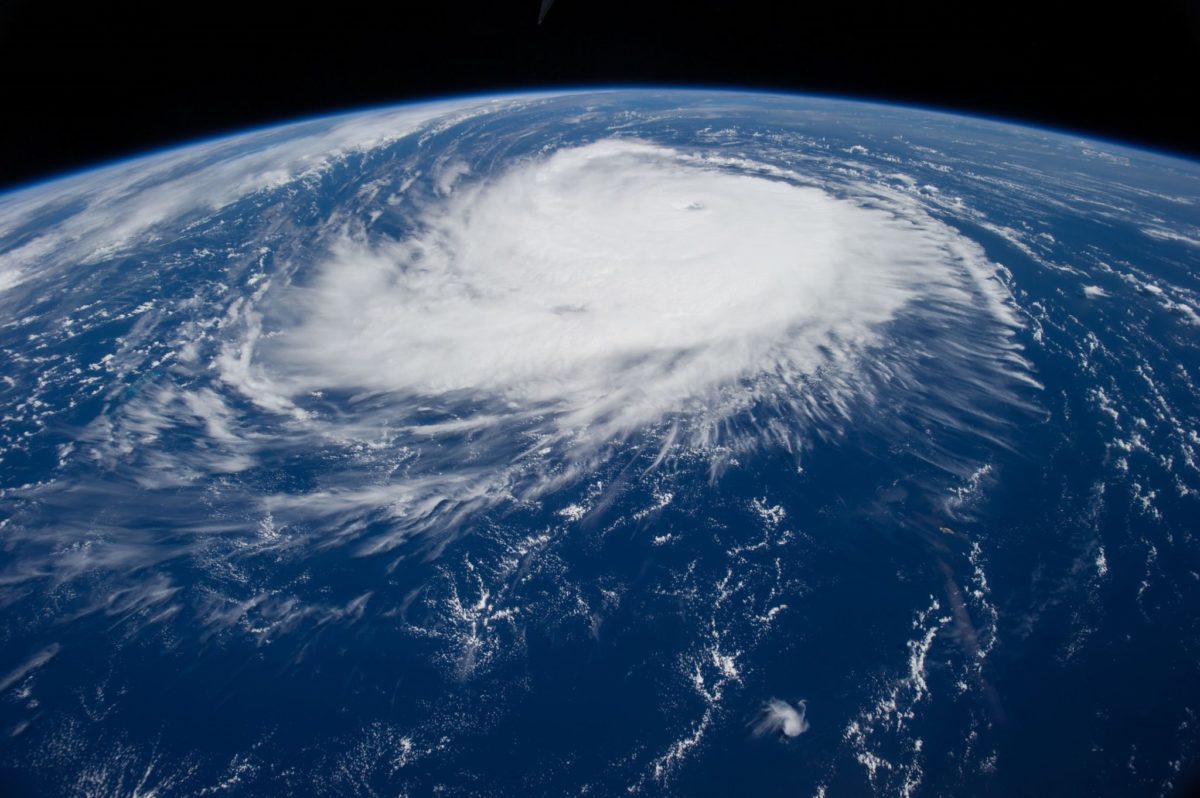

Things like hurricanes and floods are scary. When our kids come to us with questions, how do we calm their fears?

Focus on the Family touched on that in their article about talking to kids about natural disasters.

1. Assure them of your presence

We can’t control the natural disasters our families might face. But we can reassure our kids and address their fears, explaining how rare these events are and that we will do everything we can to keep them safe. When the Colorado wildfires were a bedtime concern for my daughters, they seemed relieved to know that their parents had a basic understanding of what our family would do if the fire ever came near our house. We talked about the ways we would find out if fire was approaching and the decisions we’d make if we got an evacuation notice.

The girls chatted about which (special) toys they’d take with them and agreed that we’d have to remember our dog, the blankets that Grandma made and the computer that stores the family photos. They were comforted by the assurance that their parents had a plan and would be with them.

Can we guarantee physical safety to a worrying child? No, not this side of eternity. But maybe that kind of promise isn’t what our kids really need. Children’s television icon Fred Rogers, who frequently wrote about parenting topics, once pointed to a British study about children who had survived the London bombings during World War II. According to the study, kids who were allowed to stay with their parents — even if that meant being in the city — suffered less stress and psychological damage than kids who were separated from their parents. The results, Rogers wrote, suggested that the “most immediate and urgent concerns” of young children “have more to do with the consistency of close relationships than with events — no matter how ‘traumatizing’ adults may believe those events to be.”

Rogers told the story of a kindergarten teacher from a Midwestern town. The teacher knew that her students had been exposed to media coverage of nearby tornados, and she felt it would be appropriate to honestly discuss the topic with her class. She was a bit surprised at how attentive her students were — but only until she told them that if a tornado came near their town, she would do everything she could to keep them safe until their parents arrived. “After hearing what they really wanted to know,” Rogers concluded, “they seemed to lose interest in the whole question.”

2. Don’t avoid the faith implications

Sarah Hilgendorf, a mom and editor at Focus on the Family, says that most of the conversations she had with her daughter, age 7, during the Waldo Canyon wildfire of 2012 didn’t really have to do with fears about the safety of her father, who serves as a Colorado firefighter. “She was used to him heading off toward various fires, and she didn’t really have context for how different this particular fire was,” Sarah says. “But she really wanted to know why God wasn’t intervening to stop the fire. I found her in her room, crying. She’d been praying, and she thought that God must not be listening, or that He didn’t care.”

Natural disasters can seem incompatible with our view of a world created by a loving, all-powerful God. Can’t He control the weather? Can’t He stop the terrible storms, or at least protect the people who can’t get away? And these aren’t questions that only children ask. Parents, pastors and theologians have wrestled with this issue over the centuries.

Apologist Alex McFarland, author of The 21 Toughest Questions You’re Kid’s Will Ask About Christianity, says that it’s important for parents to respond as honestly as they can to these questions from children, to help them recognize that natural disasters are a part of life and are compatible with their growing faith. “Our children’s questions in these areas deserve thoughtful, logical responses,” McFarland writes. “It’s not sufficient to simply write off disasters or hardships by saying ‘God works in mysterious ways.’ ”

As you discuss these questions with your kids, remind them that this world has been sickened by the consequences of sin. Creation, the apostle Paul wrote, continually suffers the pains of its “bondage to corruption” (Romans 8:21). It can be helpful to return to Genesis, to help kids see that the world was created without disasters and destruction, that sin brought all death into this world and that the infection remains to this day. “God says that the original creation was perfect,” says McFarland, “but sin and fallenness was introduced through human rebellion. It was our sinfulness that caused God to curse the earth.”

The story doesn’t end there, however. While God may not always calm the wind and the waves, He doesn’t sit back and ignore our plight. Just as He sent His Son to save us, He also has promised to redeem this fallen world, to “make all things new” (Revelation 21:5). He has promised that He will never leave us or forsake us (Hebrews 13:5), even if this corrupted and dangerous, natural-disaster-burdened world seems set against us.

3. Know when to turn off news coverage

News coverage is a big part of our culture’s conversation whenever a disaster hits. We’ve probably all heard about the importance of sheltering young kids from the excessive media coverage surrounding natural disasters.

During Hurricane Katrina, Amy Delery’s home was covered by four feet of water. Her husband, a New Orleans police officer, had to stay behind to keep order in the city, but Amy and their two daughters evacuated. She says, “Of course we prayed, but in addition, I felt it was important for our daughters to know that they were safe, at least as safe as I could help them feel. Although I desperately wanted to listen to all news reports on the car radio, I minimized the number of reports they heard, so we only listened occasionally. I did the same with the television news at the hotels along our evacuation route.”

The graphic imagery, reports of destruction and death counts can be particularly distressing to children, especially young kids. And often, there’s little new news — just repetition, empty speculation and endless looping video clips of destruction. Andy Crouch, executive editor of Christianity Today, calls this the “ironclad logic of continuous broadcasting,” that “someone must always be saying something even when there is nothing new to say.”

I don’t think we should protect our kids from all media coverage, however, particularly as they get older and can handle limited amounts, along with conversation. I’d rather have my kids see the truth, the gritty reality of a real forest fire or hurricane instead of the wild fantasies they may hear about from their school-yard friends (or from The Wizard of Oz).

4. Show them people who are helping

And it’s not all bad news. On TV, we see firefighters and pastors helping to ease pain, and national and local leaders sharing thoughtful reflection or asking for assistance. The media can help our kids connect to their community, to know that people are working together to help and protect, save and salvage.

As Fred Rogers once said, “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’ ”

As a family, you can take this one step closer to home. Sarah encourages parents to “brainstorm ways to help disaster recovery efforts. Obviously, young kids can’t help dig through burned-out or flooded rubble, but they might gather a few stuffed animals to donate to victims, help grocery shop for pantry donations or make cards and offer prayers for the people affected.”

She then suggests that parents gather news stories from a similar event that happened months or years earlier, specifically looking for follow-up stories. With them, parents can concretely show children how affected communities have rebuilt and overcome their challenges, and how neighbors and local businesses have come alongside those who have lost their homes and possessions.

This approach helps kids understand that the disaster and its immediate aftermath are not the end of the story. Because of good decisions by individuals and businesses, help for these communities often continues long after the disaster story is no longer in the news. This realization — and knowing they can help others — instills the hope in kids that things will not remain sad or scary forever for families touched by a disaster.

[x_button shape=”rounded” size=”regular” float=”none” href=”https://kvne.com/category/kvne-blogs/as-heard-on-89-5-kvne/” info=”none” info_place=”top” info_trigger=”hover”]READ ALL HEARD ON AIR BLOGS[/x_button]

0 Comments